Money Avoidance

Last week, I held a Zoom workshop on saving and investing for a group of women in their late thirties and early forties. The group included two doctors, two lawyers, and a medical researcher. They were all married with children. A quick poll confirmed their knowledge of the "saving and investing" topic was minimal. It boiled down to knowing they contributed monthly money to a retirement plan through work; that is all.

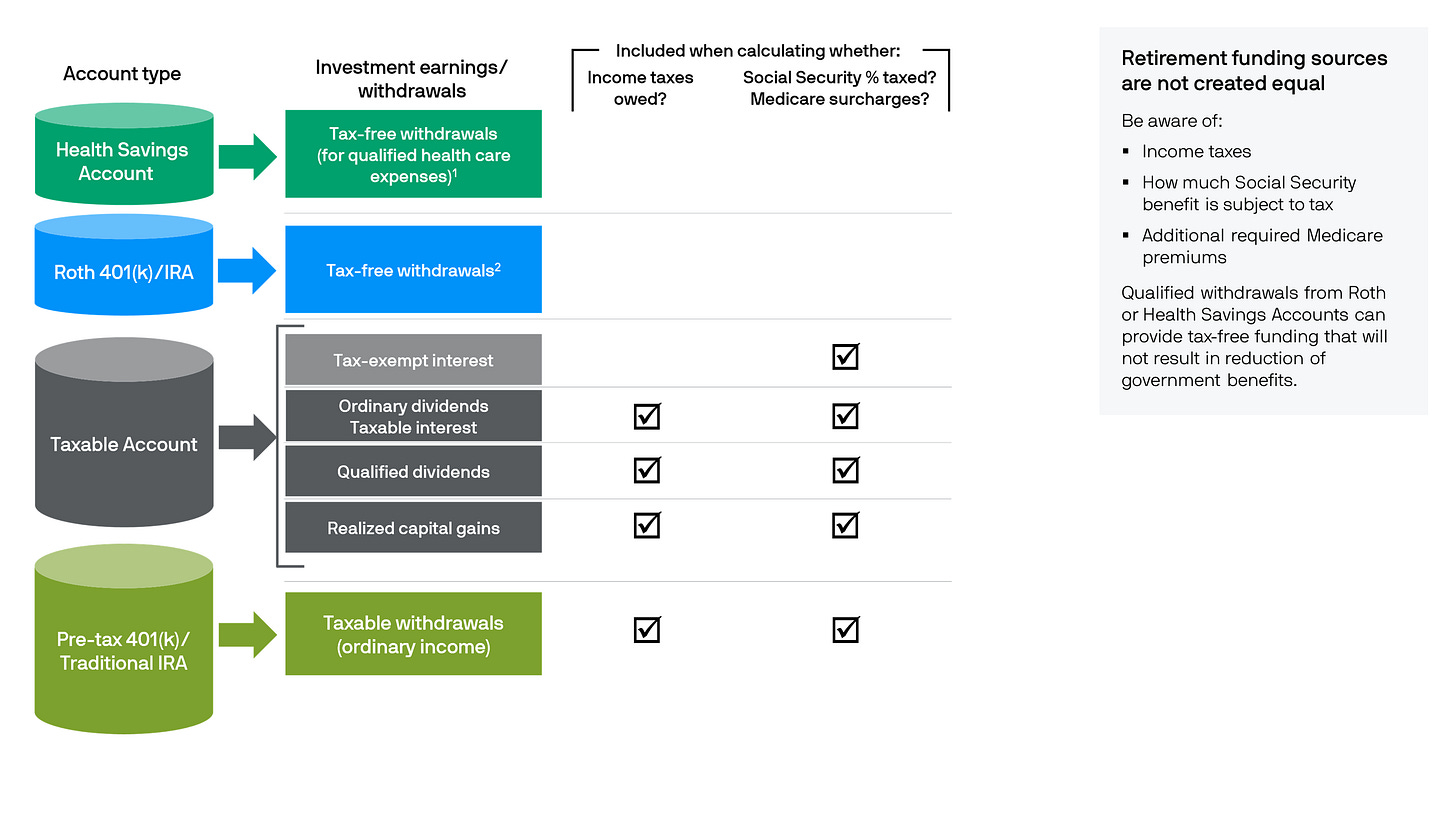

I had a PowerPoint presentation ready. But, after the poll, I decided to focus on one slide. The slide showed six types of savings accounts: a Roth 401(k), a Roth IRA, a pretax 401(k), a traditional IRA, a taxable account, and an HSA. But before I could describe each account, the women began to pepper me with questions: Why would I contribute to a Roth 401(k) instead of the pretax option? Can I contribute to a Roth or traditional IRA even though I contribute to my 401(k)? How and where should I invest my savings in my bank account? I have 401(k)s at past employers; what should I do with those? How should I invest the money in my 401(k)? Is it ok that I am in the default fund in my 401(k)? If I open an IRA, how do I invest it? Each answer I gave elicited more questions.

I was not surprised at how little these women knew about money. I see it over and over again in my financial planning practice. Women often lack financial knowledge, regardless of education, race, age, or work experience. At one point, I paused the discussion and asked: who handles the finances for your families? In all cases, it was their husbands. One woman was divorcing. Her husband made a spreadsheet of their assets for the attorney. She saw they had Roths, IRAs, 401(k)s and didn't know what any of those accounts were, let alone how much was in them. The women admitted they spent the money. Their husbands handle everything else: the bill-paying, investing, and budgeting.

After the workshop, I tried to analyze again why so many women ignore their money and avoid it. One reason could be a lack of personal finance education in our schools. Another factor could be our ingrained gender roles. They say men handle money; women handle the household.

I thought about my relationship with money. I grew up in a middle-income household with five siblings. My father made the money, and my mother raised the kids. My father was so frugal you would think we were poor. I went to a San Francisco grammar school. It had both middle-class and wealthy neighborhoods in its boundaries. I ended up with many friends who had more than I. They had weekly allowances, separate bedrooms, matching china, and fridges full of deli meats. They also had housekeepers and nannies. In college, my childhood friends recruited me into a sorority. I knew nothing about sororities. No one in my family had been in the "Greek system." I met more friends with loftier lifestyles there. This time, it was BMWs, summer homes, and designer clothes.

After I started working, I became a fan of personal finance. I knew I could do better if I became smart about money. So, aspiration and desire drove me to learn about money. I felt that if I didn't know how to build wealth, it wouldn't happen.

That could be another answer to the dilemma of women who often avoid money matters. Maybe the women in my workshop grew up with no catalyst to learn about saving and investing. Perhaps their fathers handled the money. Then, there would be little time to focus on finances when getting their degrees and credentials. Then, getting married, it was natural to have their spouses take on the role that their fathers did. Then, when the kids came, who had time to do anything else but juggle the career with the family's needs?

I thought about what I avoid, like the women who avoid money matters. For me, it is anything mechanical. If the garage door malfunctions, I immediately ask my husband to fix it; if my bike tire goes flat, the same. The TV remote drives me crazy—what are all those buttons for? I force myself to deal with the problem if my husband isn't available. I feel accomplished and proud if I resolve the issue.

As the workshop progressed, I saw how excited the women were to be getting answers to their questions. They had a thirst for knowledge. Based on our discussion, I knew that at least one of them would take action based on our discussion. I also knew it would make them feel proud and accomplished. That felt good.